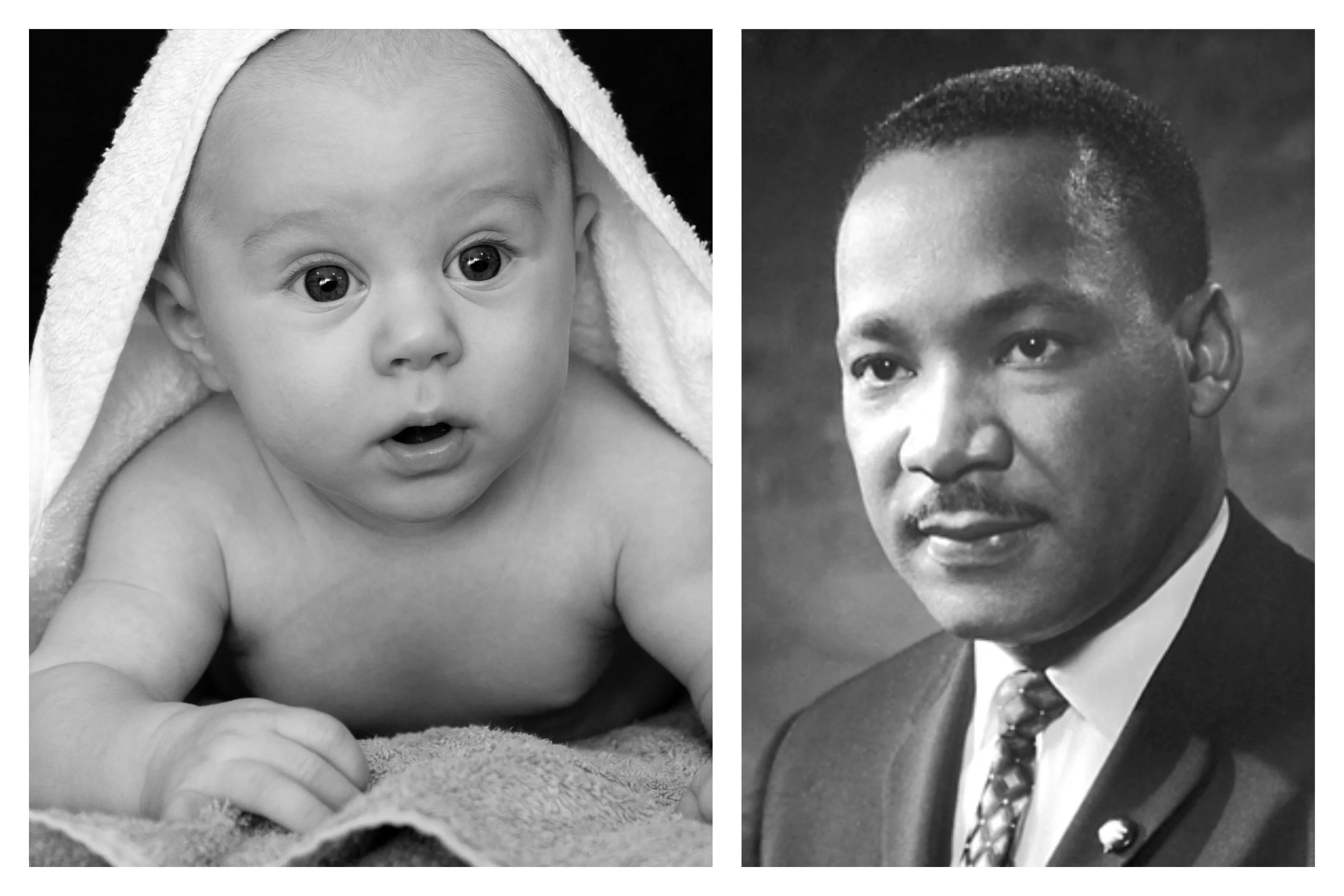

MLK and Human Life: A Divided Church

Editor: This article originally appeared on Robert J. Mayer’s personal blog. It is now shared on ACV at his request.

We’re just through the Christmas season (and our fellow Anglican and Orthodox Christians celebrate a bit longer than the rest of us do). Winter break is over for schools. Most of us are trying to get back to normal and deal with holiday debt. Congregations begin to look ahead to Easter, which comes a bit later on the calendar this year.

Then we come to the third week of January and an interesting juxtaposition of events. The third Sunday of the month is Sanctity of Human Life Sunday with an annual pro-life march in Washington, DC and events that call attention to the destruction of human life through abortion. The third Monday of January is the Martin Luther King holiday, a national holiday signed into law by President Ronald Reagan to call attention not only to Dr. King and his work, but to the stark reality that for most of our national history, African-Americans were brutally treated through chattel slavery and the horrendous discriminatory practices through what came to be termed “Jim Crow laws.” And our fellow citizens who are African American continue to face the generational impact of that brutality.

One or the other?

I could go on about both of these hideous practices. However, my purpose is to think with you about something curious that I find in American Christianity when it comes to these two events. I have observed that most congregations will call attention to one of these commemorations but not the other. Most predominantly white churches of an evangelical bent will commemorate Sanctity of Human Life Sunday with special sermons and participation in anti-abortion events designed to call attention to the thousands of human lives brutally ended through abortion. But I’m willing to bet that few of those same congregations, especially in the American South where I live, even mention the King holiday despite that Dr. King led a deeply Christian movement to end the disenfranchisement of an entire people.

Not to be outdone, most white churches of a more liberal bent often commemorate the King holiday with similar activities—special sermons that call attention to the brutality of racism and participation in activities that invoke the need for continuing the struggle for full inclusion of African Americans (and other persons of color) in the mainstream of our society. And there is little doubt that racism has morphed into something more subtle but just as pernicious. At the same time, I’m happy to wager that in most of these congregations, little if any mention is made of the Sanctity of Human Life Sunday, despite the reality that the Christian faith places human life at the center of its Christian ethic. I wonder if the discomfort those folks feel when abortion is mentioned is the same discomfort their forebears felt when the topic turned to slavery. (My African American Christian friends mostly care about both, and they don’t draw bright lines between them.)

Who is the other for American Christians

Yale theologian and ethicist Miroslav Volf has written a profound book titled Exclusion and Embrace (Abingdon, 2001). In it, Volf demonstrates how in any society there are always those we see as other. Those classified this way by the larger group are the ones who are bullied on the school-bus, the ones whom we think nothing of killing with drones, the ones for whom we find excuses to deny full humanity. We do it in our day and time through vehicles like politics and theology. You have heard it before. The ones who embrace Dr. King’s work are the liberals and liberals deny the essence of the Christian faith. Or, the ones who protest abortion on Sanctity of Human Life Sunday are nothing more than narrow-minded fundamentalists who want to tell everyone else how to live. Our political and theological ideologies shape whom we see as other.

This tells us an inconvenient truth about American Christians: that every one of us has some group of individuals whom we designate as other. My guess is that this is true for almost everyone, Christian or not, around the globe. It is as true for the movers and shakers gathering this week in Davos, Switzerland. It is true for many of those who want to outlaw almost all immigration in this country. It is true for many evangelicals who want to pretend that we fixed all of the civil rights problems in the 1960s. It is true for theological liberals who deny humanity to those children waiting to be born.

I think Christians, no matter their persuasion, need to reach beyond these ideologies. We start by identifying who is other for us as individuals and as communities. That does not mean we always agree with how they see the world, but it does mean that they are individuals for whom Christ died and who need to hear of his forgiving love. I’ve been asking who is other for me, and I must confess that the answer I hear is one that I don’t necessarily like. But, my Lord Jesus Christ did not tell me to love everyone else except for those I see as other. I think the gospel is for people of a variety of political persuasions—Democrats, Republicans, Independents, Socialists, Libertarians, and the list goes on. We now live in a world so fragmented that many see those who disagree with them as other.

We will not address this overnight, and I don’t pretend that this is easy. But here is a way that we might start. How about next year, January 2020 as the presidential primaries begin, we mark both the King holiday and Sanctity of Human Life Sunday in our churches. Some folks will get mad, but that is fine because oftentimes our anger is an important first step toward unmasking our idolatries. That leads to conviction of our sinfulness in this matter. Why don’t we use both to address this matter of the other and the overt and covert ways we dehumanize those whom we categorize this way. Both events teach us that throughout American history, groups of human beings have been denied their full humanity as people who (imperfectly, as with all of us) reflect the image of God. Wouldn’t be great if on the third Sunday of January next year we would mark both of these events by using Martin Luther King’s haunting words from Memphis on the night before his death to call attention to the work we have to do as the people of God?

Now that would be something I think the Triune God would bless.