The Fragmentation of the Christian Worldview (4/4)

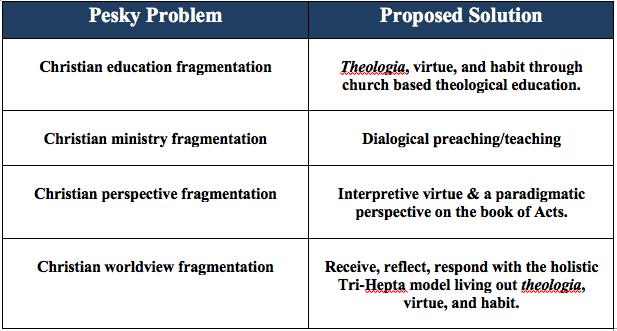

As we come to the end with this last post, we have covered the problem of fragmentation by…well, fragmenting the problem into four parts and offering suggestions for how to put humpty dumpty together again in each section (see previous posts Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, and the end of the article for a link to the full pdf). This final contribution will not rehash or summarize the previous posts, but will instead add a more practical tool to tie the major concepts together.

A pastor may preach his heart out on parenting principles from the Bible, or, how to remain single and holy for the Lord, or, why God hates divorce, but give it enough time and he will soon discover that few people seem to respond righteously with lives attuned to God’s Will. Is this merely the sinful nature? The authors of Shaping The Christian Life perceive our dilemma: “We write fragmentation into our souls.” They go on to explain the cause and calamity of inner fragmentation which twists the religious affections and outer fragmentation which erupts into our relationship with God and others (P. 36f). There is no escaping it, fragmentation is part of who we are as fallen humanity, that’s true. But is this the whole story?

While much of what we have laid out so far is absolutely relevant to the category of worldview fragmentation (e.g. bloom’s taxonomy, dialogical teaching, hermeneutical principles and humility), Barna points us in the direction we need to examine next.

What We Think Matters

Barna says only half of Protestant Pastors even have a biblical worldview, followed by just 17% of practicing Christians, and less than half of 1% of those 18-23. This is not just a divide between what we know and what we practice, this is a divide between what we don’t know at all and how we live in light of that blinding ignorance.

In another study Barna says, “fewer than two out of 10 churchgoers feel close to God on even a monthly basis.” So, 80% of church goers are not feeling, sensing, or experiencing, the presence of God or the blessings of the Word in their lives on a regular basis? While Christians will have seasons when that is true, it’s not supposed to be the norm! This is a serious disconnect between knowing and feeling.

All of this and what follows concerns how we view the world around us. J. P. Moreland defines the vital concept of worldview for us: “A worldview is a set of beliefs [and presuppositions] a person accepts, most importantly, beliefs about reality, knowledge, and value, along with the various support relations among those beliefs, the person’s experiences and the person himself.” As we will see, the typical definitions by theologians and philosophers is inadequate to the task of solving its own dilemma simply because “worldview” is actually more expansive than many are willing to allow.

How We Think Matters

The average Christian often gets lost and bewildered when moving from biblical text to biblical principles to life application (after all, isn’t that the pastor’s job in the sermon!). The ones that are connected to the faith often get the “what” to think pretty quickly, but not usually the “why,” and certainly not the “how” to think biblically.

How, for instance, should a Christian think about pop-psychology that has infiltrated the church? What exactly is “Christian” about degrees in Christian counseling anyway? What’s the difference between biblical counseling and Christian counseling and why does it matter? As one who has received years of Freudian therapy during adolescence, and later with Christian psychologists and therapists, I can tell you these Christians had little to no idea how to incorporate anything from God’s Word into their sessions. They were in practice no different than the godless models they purported to stand in stark contrast against.[1] CCEF was founded with the mission to restore this fragmented picture and offer the alternative of biblical counseling to the church. Whether they are succeeding or failing is left for others to decide, but they are certainly putting forth a herculean effort that should be role modeled by others.

Or we might ask, how does a faithful Christ follower think about politics? Darrell Bock wrote, “How Would Jesus Vote? Do Your Political Positions really Align with the Bible?” To help Christians think biblically, but sadly, most will likely put it down the moment he says something that does not agree with their pre-conceived political ideology. Most Christians are far too used to responding to political issues with their default political party rather than the declared Word of God. They tend to be reactionary rather than thoughtful (James 1:19; 3:17), and belligerent rather than gentle (2 Tim. 2:25; 1 Pet. 3:15). Paul’s admonition to Titus is all but lost in a world of shock jocks and political pundits competing for ratings as Christians cheer them on:

Remind them to be submissive to rulers and authorities, to be obedient, to be ready for every good work, 2 to speak evil of no one, to avoid quarreling, to be gentle, and to show perfect courtesy toward all people. 3 For we ourselves were once foolish, disobedient, led astray, slaves to various passions and pleasures, passing our days in malice and envy, hated by others and hating one another. 4 But when the goodness and loving kindness of God our Savior appeared, 5 he saved us…(3:1-4; emphasis mine).

More importantly then, how should a believer think about truth? One author rightly notes that the Christian ought to be searching for sapiential truth (i.e. wisdom based truth). He quotes approvingly Ellen Charry, By the Renewing of Your Minds: The Pastoral Function of Christian Doctrine:

Sapiential truth [i.e. “engaged knowledge that emotionally connects the knower to the known” p. 4] is unintelligible to the modern secularized construal of truth. Modern epistemology not only fragmented truth itself, privileging correct information over beauty and goodness, it relocated truth in facts and ideas. The search for truth in the modern scientific sense is a cognitive enterprise that seeks correct information useful to the improvement of human comfort and efficacy rather than intellectual activity employed for spiritual growth. Knowing the truth no longer implied loving it, wanting it, and being transformed by it, because the truth no longer brings the knower to God but to use information to subdue nature. Knowing became limited to being informed about things, not as these are things of God but as they stand (or totter) on their own feet. The classical notion that truth leads us to God simply ceased to be intelligible and came to be viewed with suspicion (emphasis mine).

So, the Christian seeks truth to know God and to worship Him with all of their life (Jn. 4:24). Transformative truth is not found in propositions, but in persons, namely, the three persons of the Triunity and in obedience to the Son’s way of life (Jn. 8:31).

Vanhoozer’s acclaimed The Drama of Doctrine develops all of this with far more technical finesse calling doctrines “life-shaping dramatic directions” of which the church participates in and acts out for the world to see. He approvingly quotes another,

“Doctrines serve as imaginative lenses through which to view the world. Through them, one learns how to relate to other persons, how to act in community, how to make sense of truth and falsehood, and how to understand and move through the varied terrain of life’s everyday challenges.”

Furthermore, a biblical worldview cannot merely articulate one’s view of the world derived from one’s parents, one’s faith community, one’s political allegiance, or the social sciences. Instead, “Trust but validate,” says the old Russian proverb. Or as Solomon said, “In a lawsuit the first to speak seems right, until someone comes forward and cross-examines” (Prov. 18:17, NIV). “All truth is God’s truth,” but determining what is true takes wisdom.

Wisdom is the skillful application of God’s truth to all of life to bring Him glory and to bring us good. Yet, it is first found in the fear of God (Prov. 9:10), then forged through testing (Rom. 12:2; Eph. 5:10) and sharpened through the church community (Prov. 27:17; 2 Tim. 2:25). This is true orthodoxy, not merely an informational checklist of beliefs that help us develop a biblical worldview, but a holistic inventory of the self before a holy God.

What We Feel Matters

Someone has pointed out “we do not have a soul, we are a soul.” When we speak of “soul” here we mean to speak the way Scripture predominately represents the idea, as a whole person, not just as a mere part of a person that makes up the “real self” while the body is simply a shell to occupy. That idea came from the Greek Philosopher Plato and heavily influenced the Early Church Fathers. The medieval theologian Thomas Aquinas understood the biblical emphasis on the unity of the person saying, “Man is neither his body nor his soul.”[2] He goes on to explain that a person is in fact the result of the union of both body and soul together. In Genesis God creates Adam’s body, then breaths into him the breath of life, the result of this combination is literally called a “living soul” (Gen. 2:7) and refers to the totality of the self.[3] This ego, or self, was designed for greater purposes than it is currently being used for in this present world.

He is the Potter, we are the clay. The LORD formed us with the original intent of filling us with the water of never-ending life, but when we sinned we were filled instead with the dirt of our own ignominy. We were created for immortality, but we are used for mortal purposes. Still, our shape, our purpose, our longing, our deepest desire is for something that stretches beyond this temporal plane. 17th Century mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal turned his creative genius onto examining humanity’s inner cravings:

We sail within a vast sphere, ever drifting in uncertainty, driven from end to end. When we think to attach ourselves to any point and to fasten to it, it wavers and leaves us; and if we follow it, it eludes our grasp, slips past us, and vanishes for ever. Nothing stays for us. This is our natural condition and yet most contrary to our inclination; we burn with desire to find solid ground and an ultimate sure foundation whereon to build a tower reaching to the Infinite.[4]

So wise old Solomon rightly tells us, “…he has put eternity into man’s heart…” (Eccl. 3:11). But what does that mean in the real world?

If we were to search ourselves deeply we might discover that when we find love there erupts within us a desire not just for it to continue on, but to continue on forever and ever and ever. We all want acceptance for who we are, and if we are honest, what we really want is a kind of eternal acceptance. We want pleasure, yes, but we are driven by a deeper desire to hold onto that pleasure as long as possible because we really crave an everlasting pleasure. And so, a young couple gets married after keeping themselves pure for many years. They enjoy all the sexual delights of marriage and spending endless time together. Yet, the pleasure of sex satisfies momentarily until one or both want more than the other can give. Time together is interrupted by life’s demands. Children, work, financial strain, all rain down into their life. Conflict arises because one or both try to make the other person their personal savior who will love them, accept them, need them, want them, cherish them, prize them, validate them, unto the ages of the ages. When they do not get these deep soul cravings they become angry, distraught, grumpy, moody, and the like. They are told by other Christians that they are being selfish for wanting these things, but it is not sinful to want them, desire them, or passionately pursue them, only to want them with the wrong object of our affection. Seeking to fulfill these eternal desires with anyone or anything other than Christ is idolatry. Seeking it from Christ is worship since only in this context are we giving back to him the infinite desire He is worth.

Some use these cravings of the self to argue back to the conception of God, called The Argument From Desire. Pascal reasons,

"What else does this craving, and this helplessness, proclaim but that there was once in man a true happiness, of which all that now remains is the empty print and trace? This he tries in vain to fill with everything around him, seeking in things that are not there the help he cannot find in those that are, though none can help, since this infinite abyss can be filled only with an infinite and immutable object; in other words by God himself."[5]

C.S. Lewis simplifies the argument, “If we find ourselves with a desire that nothing in this world can satisfy, the most probably explanation is that we were made for another world.”[6]

Indeed, try as we might nothing in this world will quench the black hole of infinite longing within us that can swallow whole galaxies. On the very first page of St. Augustine’s famous autobiography, The Confessions, he says, “Great are you, O Lord, and greatly to be praised; great is your power, and your wisdom is infinite…You awake us to delight in praising You; for you have made us for Yourself, and our hearts are restless until they find their rest in you.”

Here we see a longing for the kingdom of God woven into the fabric of the soul by God himself. Who we are and who we are called to be are in tension then, conflict, and hostility toward one another, until we align ourselves with God by faith in Jesus Christ and until He rescues us from this temporal corruption. The unquenchable cravings of our body, soul, mind, heart and spirit, i.e. our total self, cries out to be made whole once again. These are often identified as our existential needs, that is, the things we need to exist and truly, vibrantly, live in this world. Christian philosopher Clifford Williams lists thirteen different existential needs:

“We need cosmic security. We need to know that we will live beyond the grave in a state that is free from the defects of this life, a state that is full of goodness and justice. We need a more expansive life, one in which we love and are loved. We need meaning, and we need to know that we are forgiven for going astray. We also need to experience awe, to delight in goodness and to be present with those we love.”[7]

What’s the point of all this? Christians have long said, “Belief determines behavior,” and, “You are what you think.” It’s the very foundation upon so much our preaching, teaching, and spiritual formation in Christian colleges and seminaries. But these writers would contend there are deeper rumblings that drive us. Eve knew and believed God and his law though once the fires of desire were stoked they pushed all her holy knowing to the side. Philosopher and theologian James K.A. Smith explains why: “our loves and longings are misdirected and miscalibrated – not because our intellect has been hijacked by bad ideas, but because our desires have been captivated by rival visions of flourishing.” The premise of his book is found conveniently in the title, You Are What You Love. He defines Augustine’s use of “heart” in his famous quote as “the fulcrum of your most fundamental longings – a visceral, subconscious orientation to the world.” He refuses to draw the false dichotomy so popular in the Christian world between agape love (sacrificial) and eros love (passionate), suggesting rather provocatively that “we could think of agape as rightly ordered eros.” The question for Smith is not whether you will love something as ultimate; the question is instead, what you will love as ultimate. Whatever that is will draw you to it, move you and motivate you towards it for better or for worse. “If you want to build a ship,” a character in a kids story instructs, “don’t drum up people to collect wood and don’t assign them tasks and work, but rather teach them to long for the endless immensity of the sea.” The failure of much Christian discipleship contends Smith, is in teaching people they can think their way to holiness or think their way to right worship or think their way to virtuous living rather “we learn to love, then, not primarily by acquiring information about what we should love but rather through practices that form the habits of how we love.” For Smith, love is a habit and it not only needs daily practice through our life rituals, but the right context. The church is crucial for healing the fragmented Christian for it “is the place where God invites us to renew our loves, reorient our desires, and retrain our appetites.” This is called orthopathos or right passions/right feelings and it is a lacking but sorely needed contribution to a holistic worldview.

How We Live Matters

Nearly a million Christians a year are fleeing the organized church (so Barna). The ones who remain behind are beginning to wonder if the preponderance of divorce, lack of generous giving to churches, increase in sexual promiscuity among Christian teens (and with it one in five born-agains having abortions!), the rate of closed churches, and the mere 2% of Christians who actively share their faith, have any power to cure the spiritual anorexia of atheism, which is on the rise, or reel back the gluttonous belly of cultural Christianity hanging ever lower over the now nearly unseen belt of truth (Eph. 6:14).[8] Ron Sider says in The Scandal of the Evangelical Conscience:

"Scandalous behavior is rapidly destroying American Christianity. By their daily activity, most "Christians" regularly commit treason. With their mouths they claim that Jesus is Lord, but with their actions they demonstrate allegiance to money, sex, and self-fulfillment."

When the Apostle Paul passed on his rich theology to the churches it was not merely head knowledge he was conveying, “but also our own selves” he says (1 Thess. 2:8). His life was such a living testimony of integrated theology that he could say “be imitators of me, as I am of Christ” (1 Cor. 11:1) and charge Timothy to set forth a living example for his congregation (1 Tim. 4:12). So, orthodoxy is not merely right doctrine but right thinking, and orthopathos is right feelings, but Paul cared about more still, orthopraxy, or, right living. He tells Timothy the instructions in his letter are to teach people “how one ought to behave in the household of God” (1 Tim. 3:15).

The didache (ethical teaching) we discussed in the first part of this series was more than concepts it was concrete change. C.H. Dodd understood this, saying, “For Christianity, ethics are not self-contained or self-justifying; they arise out of a response to the Gospel.”[9] In this sense, the indicative always precedes the imperative (i.e. our identity in Christ precedes our obligations to Christ). Dodd’s articulation of the relationship between kerygma (proclamation of the Gospel) and didache (living out the Gospel) is good though it is not a fully integrated whole. For this Ridderbos, a Reformed theologian, is superior. He articulates the relationship between the two, arguing that while the two are different, the didache always presumes and includes the kerygma and fleshes out its implications.[10] Christians need the Gospel preached to them so we can remember who we are and live in accordance with our call.

Towards A Holistic Worldview: The Tri-Hepta Discipleship Model

A worldview, we are discovering, is more than conscious and unconscious presuppositions we hold about the world, or a list of propositional statements we believe about the world formal or informally declared. We might rather fill this out a bit more by saying simply that a worldview concerns how one receives, reflects, and responds to the world around them. This whole process is what I would term the practical expression of Farley’s theologia discussed in part 1.

How does one see the world, through what lens and in what categories? (Receive) How does one process the ideologies and philosophies of the world? (Reflect) And what is the result of that filtering? (Respond) Do they think in new patterns? Do they feel in new ways towards new things for better or for worse? What action is taken in response and is that action consistent with one’s worldview or does it betray a deeper more controlling subconscious worldview?

On this last point we might envision someone who believes in the need to be healthy, let us say, who has read all the stats and knows all the arguments and agrees whole heartedly with firm conviction, yet, they never exercise or consume healthy foods themselves. In this sense, their actions betray a hidden worldview more accurate to their life than their propositional beliefs. When we wrap all this up and include the many concepts we have already been working with in this series we can represent them in a single discipleship model that shines the way forward through the darkness of worldview fragmentation.[11]

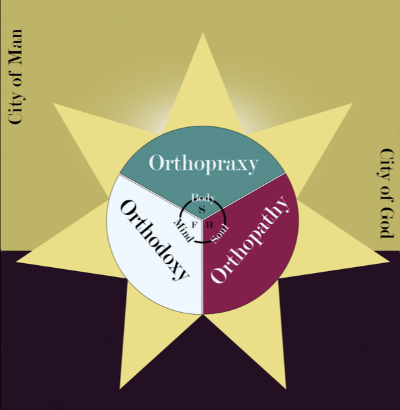

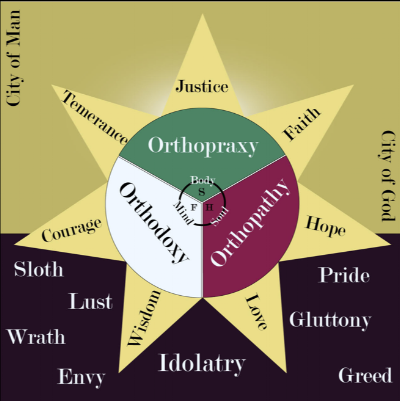

The categories are familiar to most pastors and teachers yet deceptively simple. We could take a book length walk through the full depth, but we will offer a more surface overview instead. The image of the rising sun is the church collective, “the hope of the world,” as Spurgeon said, rising to fulfill her call to spread the radiant presence of Christ throughout the nations through the Gospel (i.e. making Christ’s return imminent). In the center of the sun is the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit whose harmonious community of unified persons in one God becomes our model for being made complete both as a church and as individuals. The tripartite division represents us made in the image of God with an immaterial mind that correlates to an immaterial Father, a physical form/body that corresponds to the incarnation of the Son, and an immaterial soul that corresponds to the Spirit. Of course, each member of the Trinity did not contribute their distinct image upon us in such a way, but as a memory aid it is helpful. In this sense we can say,

a. The mind is in need of renewal (Rom. 12:1-2; Eph. 4:23).

b. The body is in need of redemption (Rom. 7:23; Rom. 8:23).

c. The soul is in need of regeneration (Gal. 5:17; Jn 1:12-13; Titus 3:5-7).

These categories are meant to be practical (i.e. describe how we live and breath and have our being) rather than technical mind you (they are not about the monism, dichotomy, trichotomy debate). Nor can we press the image of course; neither God nor we are actually 1/3 each of these!

Continuing on and moving outward from this center point we see the three terms we spent time introducing in this article. Orthodoxy is right thinking and correlates to the mind (white for pure doctrine). Orthopraxy is right living and corresponds to how we practice those principles through our physical presence, our body (green for growth). Orthopathy is right affections and corresponds to our inner soul/spirit (purple for passion). Some may prefer the simpler categories of think it, do it, feel it, following the same order respectively. All three remain connected to the influence of the Trinity:

a. Orthodoxy = God the Father as the one who gives Revelation to us.

b. Orthopraxy = Jesus as the God-Man who lives it out for us.

c. Orthopathy = The Spirit as the one who affects zeal, or passion, within us.

All of them remain united into one as well, notice the subtle white “Y” that appears to divide the three perspectives, in fact, it unites them and identifies the church (and/or the particular disciple) as Yahweh’s chosen people, a holy nation, a royal priesthood (1 Pet. 2:9).

This is holistic discipleship (including then holistic theological education, or holistic ministry training) whereby the church seeks to create one who integrates theology into their body, mind, and soul. The Tri-Hepta model (a fancy way to say the 3-7 model representing its core and outer sections) also meets the five aspects of personhood developed by John Swinton: the physical, intellectual, emotional, social, and spiritual.[12]

· Physical – Life in the body.

· Intellectual – Life in the mind.

· Emotional – Life in the feelings.

· Social – Life with one another (esp. here the church)

· Spiritual – Life with God and His indwelling Spirit within us.

An incomplete emphasis on any one or two to the exclusion of the other(s) does not merely create an anemic Gospel, but a cancerous one. Alvin Reid helpfully lays out simple equations to understand this deficiency in As You Go: Creating A Missional Culture of Gospel-Centered Students:

· Orthodoxy + Orthopraxy – Orthopathy = legalism (think Pharisees doctrine/duties)

· Orthopraxy + Orthopathy – Orthodoxy = liberalism (think bleeding hearts, but despise biblical truth)

· Orthodoxy + Orthopathy – Orthopraxy = monasticism (think the recent but fallacious arguments for the Benedictine Option, also CT Is It Time…?).

However, a full emphasis on all three should result in specific godly character traits visible to those around the growing disciple. We call these the seven virtues which stand in contrast to the seven vices (seven is representative, more could be discussed, but most virtues will fit under one of these categories).

St. Augustine called the four character traits on the left the four cardinal virtues which we interpret to primarily contribute to human flourishing in the City of Man (this world). The remaining characteristics we call the three heavenly virtues and they contribute to laying heavenly foundations for the City of God.[13]

Most will not be accustomed to the talk of virtue. Karl Cliffton-Soderstrom offers this definition: “A moral virtue is a settled disposition of a person to act in excellent and praiseworthy ways, cultivated over time and through habit.” He not only sets them in contrast to the vices but shows how each virtue defeats its respective vice as well. Smith sees the implication of this for all of Christian life training and his words are worth meditation:

“…If you are what you love, and love is a habit, then discipleship is rehabituation of your loves. This means discipleship is more a matter of reformation than of acquiring information. The learning that is fundamental to Christian formation is affective and erotic, a matter of “aiming” our loves, of orienting our desires to God and what God desires for his creation.”

In doing so we become virtuous, but not because we will it into reality or cognitively comprehend some deep piece of information that changes us; learning virtue is more like practicing scales on the piano over and over again instead of learning music theory, Smith contends. How does my love get aimed and directed so that I can develop virtue? Smith presents worship as one of the major formative tools God uses to shape our desires for him. Something he takes his entire book to explain in far more detail and depth.

Lastly, of the three heavenly virtues, only love remains when Christ returns since there is no need for faith when the object of our affection is standing before us and there is no need for hope when the promises have all been fulfilled. The four cardinal virtues do not just disappear, however, since for Augustine they are all in reality expressions of love in the first place, thus tying our effort in the City of Man as something that rises with us into the City of God:

a. Wisdom – “Love distinguishing with sagacity between what hinders it and what helps it.”

b. Courage – “Love readily bearing all things for the sake of the loved object.”

c. Temperance – “Love giving itself entirely to that which is loved.”

d. Justice –“Love serving only the loved object thus ruling rightly.”

All of this - theologia, virtue, and habit bring us back once again to where we started with Farley. If we are even partially correct in our assessment that ministerial theological education is a Frankenstein of sorts cobbled together from various other dismembered parts, then not only does it seek to impress its image upon all its followers, but once we are made to look like it, we will try to do the same to others. Our ministries will then be splintered, our perspectives will be variegated, and now even how we think will be more in broken bits than single pieces.

Applying The Tri-Hepta Model

Some will see similarity in all this to philosopher/theologian John Frame’s “triperspectivalism” which he developed in his magisterial work, The Doctrine Of The Knowledge Of God. Our tri-hepta model may overlap with triperspectivalism but it has special application to discipleship and moves in a particular direction unique to developing virtue and habitus according to Farley’s critique and theory.[14] Unlike Frame who assigns no particular order to his three perspectives we believe a holistic model begins with the nature of the Triune God-head.[15] Furthermore, in contradistinction to much of Evangelical Christianity the “on ramp” as it were into the holistic discipleship model is not orthodoxy as most assume, but orthopathos, rightly ordered passionate love/desires, as we have made a case for. While the application of this is expansive we only point out only a few surface level applications to get the mind going.

Christians, in a world of 1 min. Bible lessons, or 10 min. Bible studies, the Spirit filled Christian needs to ask themselves if they are getting a balanced spiritual diet. In this sense the tri-hepta model can be used like the food pyramid to assess our intake. Too much academic study of the Word (doctrine), but not enough stirring the heart for love (devotional) or vice versa, put us out of balance. Too much talking about what needs to be done, but not enough actually doing it is like eating cotton candy that leaves the Christian with good tastes in their mouth yet no energy to run the marathon ahead. Or simply ponder one biblical truth and apply it through all spheres – e.g. you are adopted by God (Eph. 1:5).

o Feel It = I am a child of God and experience His embrace through affective worship.

o Think It = I am a child of God so I am chosen, protected, and can cast out fear/anxiety.

o Do It = I am a child of God who is free to give lavishly because my Father cares for me.

Parents, so focused on external behavior you forget that God cares about the heart? It’s time to correct your course (Paul Tripp’s recent book is a good place to start).

Church leaders, place this model over all your programs and ask e.g., “How exactly does our Sunday School program fulfill each of these elements?” The kids are learning about Jesus, but are they learning to love Jesus? This has typically been relegated to the Spirit’s work yet Paul’s model was intensive full throttle giving of himself to facilitate the Spirit’s work too. How are SS teacher’s role modeling discipleship relationships outside the classroom to the one’s they are training? As the ancient saying says, “Pray like it all depends on God. Work like it all depends on you.”[16] We can and must do more to role model a holistic Christian lifestyle for those sprouts in the faith.

Of course, a pastor with any kind of a heart for discipleship will not be satisfied with preaching/teaching that imports no affect (probably why Martin Lloyd Jones described preaching as “logic on fire,”) nor preaching/teaching that results in no effect either (though truly much of this has to do with those being hearers of the word rather than doers). This should rightly pressure any teacher of the Word to go into her closet in heartfelt prayer, to fast for spiritual illumination, and to emerge with a special dependency on Christ’s all sufficient power.

The End Of The Matter

Once again, we ask, how on earth do we find unity amidst a sea of fragmentation? We have certainly tried to lay out not only the problems, but provide super-glue-solutions to put the shards of fragmentation back into a single tea pot that we might tip-it-over-and-pour-out the soothing waters of oneness. Here we summarize our conclusions for all four parts:

Yet, the question remains, what kind of unity are we talking about? A subjective unity of walking in the Spirit together (e.g. character as the only test of fellowship)? An objective unity to propositional truth (e.g. creeds/statement of faith). A motivational unity driven by pursuing the same goal (e.g. the “essentials” of the faith)? Yes, yes, and yes to all! But these things alone will never complete us.

Only Christ can make us whole, so in the end we pursue Him, His glory, His love, His image, and His exaltation and pray we meet others on that path heading in that direction (2 Cor. 3:18).[17] “We picture lovers face to face,” says Lewis in his work Four Loves, “but friends side by side; their eyes look ahead.” In other words, true friends face the same direction and walk towards the same goal and for the Christian that goal is truth. He goes on to say,

“That is why those pathetic people who simply “want friends” can never make any. The very condition of having Friends is that we should want something else besides Friends. Where the truthful answer to the question Do you see the same truth? would be "I see nothing and I don't care about the truth; I only want a Friend," no Friendship can arise.”

And at the end of the day, after all the academic research has been done and all the theological terms have fallen silent, isn’t that the core of what we are seeking when we talk about Christ exalting Gospel unity? Namely, friendship with God (i.e. forgiveness, reconciliation, justification, glorification) and that over spilling and splashing into friendship with one another (koinonia-burden bearing, belonging, love, acceptance)? Such is found in the burning heart of Christ alone and such we must claim moving forward.[18]

Download the entire Fragmentation Series

[1] For a thorough critique of the field by a professional psychiatrist and professor of clinical psychiatry see How Christian Is Christian Counseling? By Gary L. Almy, M.D.

[2] Torrell, Jean-Pierre. Saint Thomas Aquinas, Vol. 2: Spiritual Master, 2003: 256 quotes Aquinas further saying, “Since it is a matter of an animated body, we must not speak of either of priority or posteriority; there is absolute simultaneity, since indeed the animated body coincides with the incarnate spirit.” While the soul survives death, Aquinas rightly understands that it needs the body and longs for a body since “neither the definition nor the name of person are fitting to it.” Aquinas subscribes to the false notion of the immortality of the soul, but correctly understands that only the resurrection of the body will fulfill the human longing for salvation.

[3] There is a lively theological debate on how to understand the body-soul relationship in Scripture. For a good introduction and defense of some form of unified dualism see Cooper, John W. The Current Body-Soul Debate: A Case For Dualistic Holism in SBJT 13.2 (2009): 32-50.

[4] Emphasis mine. Pascal, Blaise. The Pensées, 72 - 1932: 19-20. The title means, The Thoughts. A collection of fragments he penned that were published posthumously.

[5] Blaise Pascal, Pensées, trans. A. J. Krailsheimer (New York: Penguin Books, 1995), #148, p. 45. This is actually the foundation of his more famous apologetic argument referred to as Pascal’s Wager. If someone is unsure whether God exists or not, they should wager, or bet, that he does by putting their faith in him anyway. If they bet that God exists and come to find out He does, they gain eternal happiness. If it turns out they believed in God but are proven wrong, that God does not exist, they have nonetheless lived a good and meaningful life of love towards others. If, however, they do not take the wager, believing they can be good without God, and they are proven wrong, they will suffer His righteous wrath and holy indignation in eternal destruction of body and soul. Thus, it is a legitimate bet, and a good one, to wager God exists because doing so satisfies the inner longing for eternal pleasure and avoids eternal pain.

[6] Mere Christianity. Cf. Peter Kreft, “The Argument From Desire,” at peterkreeft.com/topics/desire.htm. “Existential Apologetis: A Survey” at cliffordwilliams.net/existentialapologetics.

[7] Williams, Existential Reasons for Belief in God: A Defense of Desires and Emotions for Faith, 2011:32. He devotes chapter two to unpacking these needs and their implication for humanity. This is an important argument for evangelism in the modern era. Williams argues that we are right to emphasize existential human longings and not merely “reason” and “evidence,” as proof of God and His truth. He identifies need as a “triggering condition” that opens the person’s mind, will, and emotions to see Jesus for who he really is, the divine God-man.

[8] Taken from a previous blog, A Call to the Indifferent published online and in the AC Witness. Also, take all studies with a tablespoon of salt. Barna and Pew Forum are respectable, but see Kevin DeYong’s blog, “Premarital Sex and Our Love Affair with Bad Stats” at thegospelcoalition.com. Though, Bill Bright founder of Campus Crusade for Christ lamented the 2% back in the 1990’s, and little has changed.

[9] Preaching and Teaching In the Early Church.

[10] See, Redemptive History and the NT. Or, read a helpful summary at Walking Together Ministries.

[11] Thank you Chase Mendoza for refining the color pallet.

[12] P. 36, Spirituality and Mental Health Care: Rediscovering a ‘forgotten’ Dimension.

[13] Augustine does not just see the city of man as normal human physical cities, but the deeper heart attitude driven by and tainted by the unholy love of self. The same is true for the city of God in opposite fashion. That means any place the love of Christ dwells (i.e. the church) becomes as it were, a sort of heavenly embassy where the citizens of the new kingdom act in accordance with their kings rule.

[14] However, Frame’s views should be seriously studied. In that work Frame uses similar triads (mainly the Normative, Situational, Existential) that do correlate to our Orthodoxy, Orthopraxy, Orthopathos in some respect though his system is far more expansive as he seeks to bring unity to secular fragmented theories of epistemology (rationalism, empiricism, existentialism) by providing a means to bring them altogether (i.e. all three perspectives are necessary). He applies this using over 100 triads in various categories in his Systematic Theology. For more see his Primer on Perspectivalism online, or more recent (and concise) work Theology In Three Dimensions: A Guide to Triperspectivalism and Its Significance). Poythress’ model of how to train leaders, via the categories of Prophet, King, and Priest also follows triperspectivalism (Symphonic Theology; see his online introduction Multiperspectivalism and the Reformed Faith). John Anderson is probably right to see Frame’s theory as less a theory of knowledge and more accurately as an analytical tool that can aid modern epistemologists in various ways (so Presuppositionalism and Frame’s Epistemology”).

If the average pastor is willing to think hard on triperspectivalism it will bear fruit for ministry application (e.g. Tim Brister shows great practical application for spiritual formation…though we still prefer our tri-hepta model).

[15] Frame argues in The Doctrine of the Knowledge of God that his view is simply "generic Calvinism." He quotes Calvin's famous line from the beginning of his Institutes demonstrating how Calvin himself believed in the interdependence of the knowledge of God and self and even admitted he was unsure which one came first (i.e. paragraph #1 of Institutes). Frame claims, “The knowledge of God’s law, the world, and the self are interdependent and ultimately identical” (p. 89). Curiously, Frame overlooks the next paragraph where Calvin concludes “it is evident that man never attains to a true self-knowledge until he has previously contemplated the face of God, and come down after such contemplation to look into himself” (paragraph #2). This would be perhaps our only major critique of Frame’s excellent ideas, namely, that there should be an order of primacy of some kind (e.g. within his system the Word of God should be eminent because it alone reveals the nature of God so that we can see ourselves in His reflection).

[16] No one knows the attribution, some trace it back to Augustine, the Catholic Church says Ignatius (CCC 2834 n. 122) but neither show evidence of such a thing (though it certainly fits the spirit which Ignatius so valued). Some may want to flip the saying to make an alternative point, “Pray like it all depends on you, work like it all depends on God.” That is, pray urgently and seriously and work with confidence knowing that God will bring the harvest. Some of you theologian-types will not be satisfied until you tinker a bit more, “Pray like it all depends on God [because it does], work like it all depends on God [because it does].” Nonetheless, the quote makes its intended point in the article (i.e. so if you are reading this stop myopically looking at the letter of the teaching and try to catch the spirit of it!).

[17] A.W. Tozer captures this well in The Pursuit Of God: The Human Thirst for the Divine, “Has it ever occurred to you that one hundred pianos all tuned to the same fork are automatically tuned to each other? They are of one accord by being tuned, not to each other, but to another standard to which each one must individually bow. So one hundred worshipers met together, each one looking away to Christ, are in heart nearer to each other than they could possibly be, were they to become 'unity' conscious and turn their eyes away from God to strive for closer fellowship. Social religion is perfected when private religion is purified. The body becomes stronger as its members become healthier. The whole church of god gains when the members that compose it begin to seek a better and a higher life.”

[18] For a great all church read on the topic of friendship see Timothy Keller’s protégé Scott Sauls’ new book Befriend: Create Belonging in an Age of Judgment, Isolation, and Fear.